At first glance, a bird’s beak might seem simple – just a tool for eating. But look closer, and you’ll discover that this single feature can reveal an astonishing amount about a bird’s life.

A beak can tell us what a bird eats, how it builds its nest, how it attracts a mate, and even how it stays cool in extreme heat. Studying bird bills has led to some of the most important scientific discoveries of all time, including evidence linking modern birds to ancient dinosaurs and insights that helped shape the theory of evolution itself.

So in this article, we’re giving bird beaks the attention they truly deserve.

1. There is a Huge Diversity of Bird Beaks

As you have probably noticed, beaks come in a whole range of shapes and sizes.

This diversity isn’t accidental. Each beak shape is finely tuned to a bird’s lifestyle and diet, allowing different species to exploit different food sources and reducing the need for competition.

Seed-eating birds like finches have cone-shaped beaks: adapted to trap seeds in the groove at the bill base and crack them open.

Woodpeckers have strong, chisel-shaped bills: enabling them to drill into tough wood to find insects and deep nesting cavities.

Wading birds like the white ibis often have long, down-curved bills: for probing deep into mud and sand, capturing invertebate prey like crayfish and crabs.

Hummingbirds have long, thin bills: perfect for reaching deep into tubular flowers and drinking their nectar.

Birds of prey have sharp, hooked beaks: built to tear into meat and rip off morsels to eat.

Crossbills have a wedge-shaped, crossed beak: especially adapted to scoop conifer seeds out of their cones.

This is just a few of the main types of bird beak. With around 11,000 bird species globally, we would probably need a whole library to describe them all!

2. Birds Can Feel with Their Beaks

We often think of a beak as a bird’s “mouth”, but technically, its just the outer covering of the mouth beneath.

A bird’s beak is made up of two main parts:

- the upper beak (maxilla)

- the lower mandible

The beak is not a part of the skull in the same way as our jaws. It is actually an extension of the skull and is not made from solid bone.

So what are bird beaks made of?

The beak of a bird in a multi-layered structure including a bony core that connects to the skull bones of the bird. The outer layer of the beak is called the rhamphotheca, and is made from keratin – the same material in our hair and nails. Like our nails, a bird’s bill grows continously thorough its life.

Beaks contain a vascular layer, supplying blood to keep it healthy and growing – and here’s something that might suprise you: they’re packed with nerve endings:

This means birds can actually feel with their beaks. They can detect textures, temperature changes and even assess food quality before swallowing their meal.

3. Beak or Bill? Potato, Potahto.

A duck walks into a drugstore to buy a chapstick. The cashier asks the duck “how do you want to pay for this” and the duck replies “put it on my bill!”

You might have wondered if there was a difference between ‘beak‘ and ‘bill‘. Generally, no there isn’t a difference, and they can be used interchangably.

However, historically, the word ‘beak’ was mainly used to describe hooked bills, like those of birds of prey. Still today, we tend to use ‘bill’ when discussing waterfowl like ducks.

4. The Longest and the Largest

Bird beaks range from delicate to downright intimidating – but which ones break records?

The Smallest Bird Beak in the World

This is a suprising one.

The title goes to New Zealand’s iconic kiwi.

“But don’t Kiwi’s have long beaks?”

From visual observation, yes, Kiwi’s seem to have a fairly long, but thin, beak.

But, if we get technical, the beak of a bird is measured from their nostrils to the tip. And kiwis have their nostrils at the end of their beak!

So technically speaking, kiwi’s have the smallest beaks in the bird world.

The Longest Bird Beak in the World

The winner here is the sword-billed hummingbird.

In fact, this is the only bird in the world who’s beak is longer than its whole body. Its impressive bill can reach lengths of up to 4.7 inches.

The Biggest Bird Beak in the World

When width and volume are taking into account, the crown goes to the toco toucan.

The colorful beak of the toco toucan has a surface area of up to one third of its total body size.

5. Before Beaks, There Were Toothed Snouts

Meet Ichthyornis dispar.

This prehistoric bird lived around 100 million years ago, in North America.

It resembled a gull-like bird with a long beak and large eyes.

But this prehistoric bird had something modern birds lack entirely: teeth

A spotlight was cast on this bird in 2014, when scientists found the first complete skull fossil of this species. Using CT scans, they revealed that this ancient animal had sharp, curved teeth and large jaw muscles.

Why does this matter?

This ancient bird could be the link between dinosaurs and modern-day birds. Scientists theorize that it was the toothed snouts of dinosaurs that developed into the toothless beaks of modern-day birds – and I. dispar may have been a crucial middle stage.

The development of beaks in dinosaurs likely replaced the need for grasping forelimbs like those of velociraptors and t-rex. Without the need of forelimbs for feeding, these limbs were freed up for a new purpose… flying!

6. Birds Use Their Beaks to Find a Partner

Beaks play an important role in bird mating and courtship.

For example, did you know that the beak color of males in some bird species becomes brighter when they are ready to breed?

Or that some birds have ultraviolet beak markings that cannot be seen with our human eyes? And that these UV colors can signal health, genetic quality or mating status to other birds?

Beaks play a role in many courtship behaviors, including:

Billing

This is where a bird couple will get rub their beaks together in an act to strengthen their bond. A well-known bird who does this is the Atlantic Puffin.

‘Beak to Beak’ Feeding

This is a behavior we often see on our nesting cams. The male bird brings food to his female partner, passing it from his beak to hers.

Beak Clattering

Beak clattering is the sound that certain bird species make by knocking their upper and lower mandible (beak) together. This makes a distinctintive noise that these species use to communicate. The white stork is a well-known species to do this.

7. Bird Beaks and the Theory of Evolution

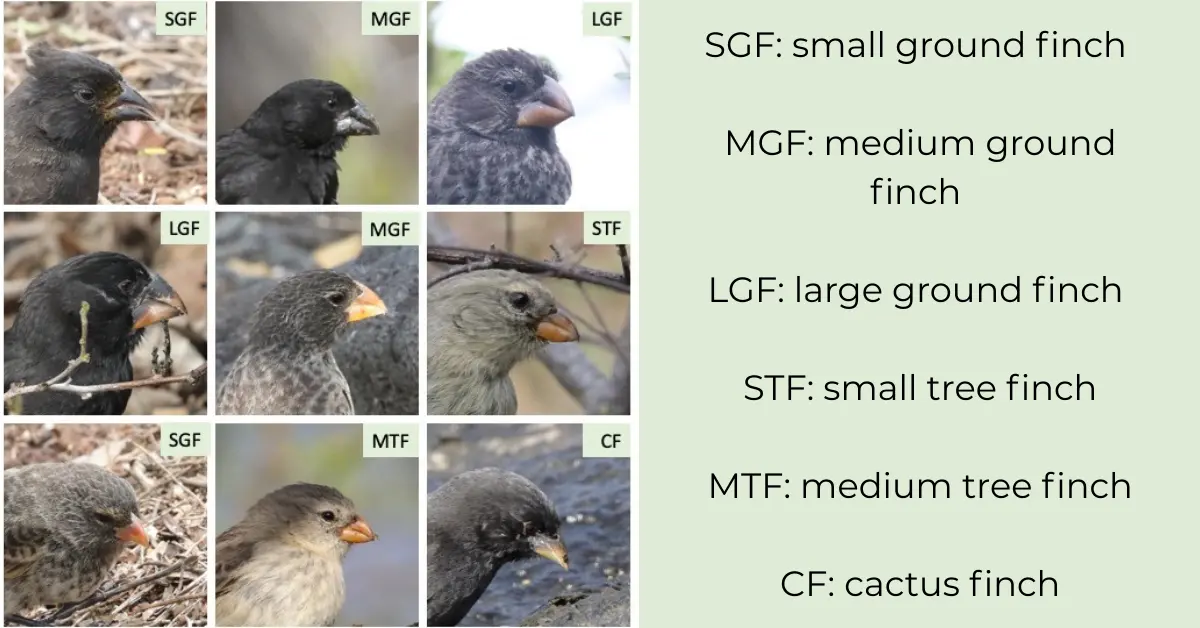

Maybe you’ve heard of Darwin’s finches?

And maybe you know that these were the birds that Charles Darwin came across in his pioneering expedition to the Galapagos Islands?

But do you know what makes this tiny birds so special?

During his visit to the Galápagos Islands, Charles Darwin observed several finch species found nowhere else on Earth. Scientists now believe these birds all evolved from a single ancestral species that arrived over a million years ago.

As finches spead across the islands, their beaks evolved to match different food sources, including:

- The vegetarian finch that has a parrot-like beak for eating fruit

- The large ground finch that has a strong, cone-shaped beak for breaking tough seeds

- The woodpecker finch that has a long, probing beak to find insects.

Studying these birds helped Darwin formulate the principle of natural selection – a cornerstone of evolutionary biology.

8. Baby Birds Have a “Tooth” on Their Beak

Baby birds hatch with something called an egg tooth.

Despite the name, this lump isn’t really a tooth. Instead it’s a temporary, hardened tip.

Unhatched chicks use this to knock on the inside of the egg, eventually chipping themselves free from their shell.

After hatching, the egg tooth has served its purpose – and soon falls off.

9. Some Birds Use Their Beaks to Keep Cool

Birds can’t sweat or seak air-conditioned rooms – so how do they avoid overheating?

Some birds, especially those found in hot countries, use their beaks to cool down.

These birds can increase bird flow to their beaks – an uninsulated part of their body with many blood vessels – allowing excess heat to dissipate.

This means that birds with larger beaks can cool themselves more effeciently.

Research has shown that birds living in hotter climates tend to have bigger beaks than those in cooler regions. Take the Toco Toucan and the Greater Hornbill – you’ll only find these big-beaked birds in tropical climates!

Where is gets even more fasincating is research done by scientist Sara Ryding on Australian parrots. She found:

- Since 1871, the beak size of gang-gang cockatoos and red-rumped parrots increased by 4-10%.

- This size increase is in parallel with climate change and rising temerpatures.

Ryding suggests that “there is widespread evidence of ‘shape-shifting’ (changes in appendage size) in response to climate change and its associated climatic warming”.

10. Why Captive Birds Need Beak Trimming

As mentioned previously, bird beaks are made of keratin – the same material our fingernails and hair are made from. And just like our nails, the beaks of birds continually grow.

Wild birds will naturally file down their beaks through their feeding and foraging habits. You’ll often see them rubbing their beaks against branches.

Captive birds often lack these opportunities. Without natural wear, their beaks can become overgrown, making feeding difficult or even dangerous.

For this reason, beak trimming is sometimes necessary for birds kept in captivity to maintain their health and wellbeing.

More Than Just a Beak

Bird beaks are far more fascinating that I first realised. Not only can their shape reveal what a bird eats, but also how it courts a mate or builds its nest and even how it has evolved over millions of years. Beaks offer a unique window into both modern bird behavior and deep evolutionary history – the humble beak is truly one of the most revealing features in the avian world.